VINCENZO CAMUCCINI ROME, 1771-1844

93 x 78 x 5 cm (with the frame)

Provenance

Barone Vincenzo Camuccini collection, Palazzo Camuccini, Cantalupo in Sabina; Eredi Camuccini, Rome

Exhibitions

1978, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844). Bozzetti e disegni dallo studio dell’artista, n. 69; 2021, Rome-Paris, I Camuccini. Tra Neoclassicismo e sentimento romantico, curated by Antonacci Lapiccirella Fine Art and Maurizio Nobile Fine Art, Rome October 1-28 2021 at Antonacci Lapiccirella Fine Art, Paris November 5-11 at Galerie Eric Coatelem, Paris November 16 – December 3 2021 at Maurizio Nobile Fine Arte.

Literature

G. Piantoni De Angelis, in Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844). Bozzetti e disegni dallo studio dell’artista, curated by G. Piantoni De Angelis, exhibition catalogue (Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, October 27 – December 31, 1978), Rome 1978, p. 37, n. 69; L. Verdone, Vincenzo Camuccini pittore neoclassico, Roma 2005, p. 134, fig. 27 (detail); I Camuccini. Tra Neoclassicismo e sentimento romantico, catalogue of the exhibition curated by Antonacci Lapiccirella Fine Arte and Maurizio Nobile Fine Arte, text by Stefano Bosi, Rome – Paris 2021, P. 41, n.16

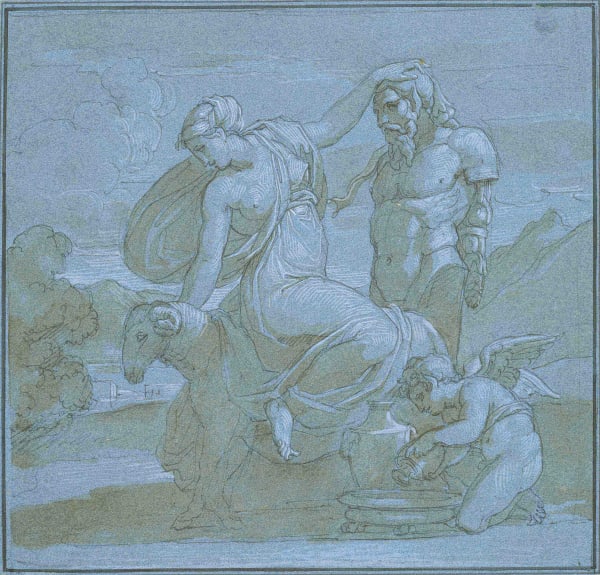

Narrated by Livy and retold by Abbot Vertot d’Aubeuf and Vittorio Alfieri in the eighteenth century,[1] the story of Virginia’s death is one of the large number of exempla virtutis which the renewed historical genre addressed from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards to reach unprecedented formal solutions and a language brimming with content.[2] The story tells of an episode of death preferred to dishonour: the decemvir Appius Claudius, in love with the beautiful Virginia, tries to take her as a slave, but her father grabs a knife and kills her, rather than seeing her dishonoured. In Camuccini’s interpretation, this chilling morality is expressed in a severe style made up of rigorously arranged marmoreal figures on a rectilinear perspective grid: a style of stoic sobriety close to David’s manifesto works, even if influenced, in turn, by the precocious neoclassicism of the illustrations of Gravelot’s Roman history and from the paintings of a similar theme previously produced by Gabriel-François Doyen (1760) and Nathaniel Dance (1761).[3]

It was at the end of the eighteenth century that the Roman artist received from one of the most prestigious British travellers and collectors present in Rome, Frederick August Hervey, Bishop of Derry and 4th Earl of Bristol, the task of executing the monumental canvas designed as a pendant to the Death of Caesar, commissioned by the same English lord in 1793.[4] Here, the manifold currents of the late eighteenth century with their didactic themes, stylistic reform, and classical allusions, were distilled into a stoic image which combines pictorial genius and moral passion. Compared to the energy and fervour present in the painting – of which the two canvases on display are respectively the preparatory study and a finished sketch of the left-hand side[5] – the previous depictions of classical virtue appear weak both in style and in ethical conviction. Their fluctuations and compromises were by now completely erased from a picture which sums up the most rigorous potential of the neoclassical form along with the virtue of the Roman Republic. The characters presented by Camuccini are animated by a vigorous assertion of willpower. In the heroic gesture of Virginia’s father, this new proclamation of moral energy pervades the body and mind, from the determined gaze of the still face to the tense muscles of the extended limbs. In dramatic contrast, the wet nurse behind him is overwhelmed by tragic grief. It is not only the composition, with its separate groupings, which decisively breaks up the unity of action, but also the style of the drawing which distinguishes between virile determination and feminine abandonment to debilitating suffering. Thus, in the group to the left of the scene, headed by the hieratic figure of Appius Claudius, the tense muscles in the expertly portrayed anatomy create contours and poses whose regular angular rhythms contrast with more malleable and flowing outlines, which, rising from Virginia’s right foot to die in her left arm, abstractly suggest an image of exasperated grief without hope.[6]

It was works like these which appeared in the eyes of Giuseppe Mazzini, art critic, among the best results born of that “classical school” – of which Camuccini, together with Giuseppe Bossi, Andrea Appiani and Pietro Benvenuti, was among the most authoritative exponents – capable of erasing, with a swipe of the sponge, “exaggeration, artificiality and mannerism” from the preceding figurative arts. The only school capable of purifying taste and infusing painting with new ideals and, on a formal level, “the finiteness, the execution [...] the perfection of the details [...] the purity of the design, the mastery of the drapery, of the canny classic groupings.”[7] An art of transition, therefore, indispensable, however, to arrive at the modern painting of national history of which Francesco Hayez would be the greatest representative; an art composed by masterful architects of a painting which believed in the civil rebirth of man and that found its Paradise Lost on the shores of Greece and Rome.

- Stefano Bosi

[1] Narrated in Book III of Ab urbe condita (verses 44-58) by Livy, the story of Virginia was recalled in 1719 by Aubert de Vertot d’Aubeuf in his Histoire des révolutions arrivées dans le gouvernement de la république romaine, in 1738 -1741 by Charles Rollinin his Histoire Romaine depuis la fondation de Rome jusqu’à la bataille d’Actium (1738-1741), and by Vittorio Alfieri in the tragedy of the same name, published in 1783 (See V. Alfieri, Vita scritta da esso, edited by L. Fassò, Asti 1951, IV, 6).

[2] On the subject, still fundamental remains the analysis present in R. Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth-Century Art, Princeton 1967.

[3] Doyen’s gigantic canvas was purchased, through the authoritative mediation of the Count of Caylus, by the Duke of Parma, Philip of Spain (Parma, Galleria Nazionale), after it had aroused Diderot’s enthusiasm at the Salon de Paris of 1760. The theme was used again the following year by Dance in a painting presented in 1761 at the Society of Artists in London and engraved six years later by John Gottfried Haid (See B. Skinner, Some Aspects of the Work of Nathaniel Dance in Rome, in “The Burlington Magazine”, CI, September-October 1959, pp. 346-349), then by Nicolas-Guy Brenet at the Salon of 1783 (Nantes, Musée des Beaux-Arts) and by Guillaume Guillon Lethière in a drawing exhibited at the Salon of 1795 which, only in 1828, would be translated into the monumental painted version now at the Louvre (See A. Imbellone, entry in Vittorio Alfieri aristocratico ribelle (1749-1803), edited by R. Maggio Serra, F. Mazzocca, C. Sisi and C. Spantigati, exhibition catalogue, Milan 2003, pp. 58-59, no. II.5). Again in 1795, Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier represented the instant - according to the indication in the Salon catalogue - “…où Virginie est appellée en jugement devant le décemvir Appius, qui donne ordre à Claudius d’enlever la jeune romaine. Mais Icillus, à qui elle était promise, vient d’enlever à ses ravisseurs et menace Appius. Munitorius oncle de Virginie écarte un Licteur qui s’opposait à son passage, et les dames romaines défendent la pudeur outragée. La scène est dans la place publique.”

[4] A detailed description of the work is given in M. Missirini, Alcuni fatti della storia romana dipinti dal Barone Vincenzo Camuccini incisi a bolino da diversi artisti e descritti dall’abate Melchior Missirini, Rome 1835, pp. 15-21. On the history of the Death of Virginia and the Death of Caesar, see the previous entry, with related notes.

[5] Compared to the painting now kept at the National Museum of Capodimonte, in these two canvases there are numerous differences in style, which testify to the long creative road undertaken by Camuccini towards the final version (See Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844). Bozzetti e disegni dallo studio dell’artista, edited by G. Piantoni De Angelis, exhibition catalogue, Rome 1978, pp. 34-37, nos. 65-69). In the preparatory study for Appius Claudius, for example, the most evident difference concerns the figure of the lictor positioned to the left of the Roman politician, caught in the act of covering his face with his left hand to avoid watching the tragedy unfolding before him. An expedient which, in the final work, Camuccini decided to change, giving the figure a more serene expression and admiration of Appius Claudius.

[6] The figure of Virginia was the object of admiration on the part of August Wilhelm Schlegel, in particular in the gesture with which she “clings to her father’s clothes in an action that betrays a childhood habit”. A. W. Schlegel, Rom Elegie, Berlin 1805, p. 99.

[7] G. Mazzini, La pittura moderna italiana, in Scritti editi e inediti di Giuseppe Mazzini, Imola, vol. XXI, p. 271.

Join the mailing list

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive all the news about exhibitions, fairs and new acquisitions!